Coup d'etat or Revolution?

Labels:

Coup d'etat,

Military,

Prem,

Sonthi,

Thaksin

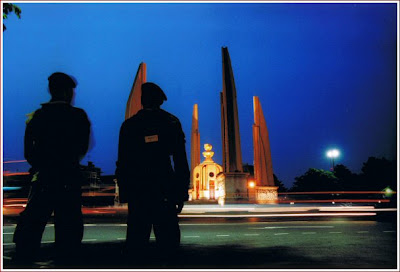

Combat troops deployed to guard against a possible counter-coup at Democracy Monument. Bangkok - September 20, 2006.

On September 19th the Thai military, lead by General Sonthi Boonyaratglin, removed Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra from power.

The event was quickly labelled a coup d’etat and the international community – particularly Western states – condemned it and lamented the break down of democratic principles.

The view from the streets of Bangkok has been rather different.

The word revolution (ปฏิวัต) has been used to describe the recent events and scenes of citizens giving flowers to soldiers seem to support the idea of a popular movement against an unpopular government.

The difficulty is that ‘coup d’etat’ and ‘revolution’ are not interchangeable terms and each describes very different events.The expression coup d’etat carries with it ideas of ruthless tyrants vandalizing democratic ideals in bloody street clashes.

Revolution, on the other had, conjures images of a people’s power movement breaking free from the iron grip of a brutal and unjust dictatorship.

If the terms coup d’etat and revolution have both been used to describe the toppling of Thaksin’s government then Thailand’s political crisis might be best understood as being a combination of both.

Was it a Coup?

The short answer is clearly ‘yes’ but the long answer is ‘yes, but…’.

Tanks did roll, combat troops were deployed, and Thaksin was overthrown by General Sonthi – that is a fact.

Yet the long answer would have to question Thaksin’s corrosive effect on democracy and the consequences of allowing him to remain in power.

Thaksin’s rise to power in 2001 as a populist billionaire was indeed a happier time in Thai democracy.

Sure, the Thai political arena is known to creatively bend the rules which results in vast sums of money exchanging hands, positions of power being doled out to cronies or family members, and blood is often spilled but there certainly are recognizable democratic traits.

At the poll booths citizens are free to choose who they like and the election process is perceived internationally as free and fair.

As Thaksin’s political problems began to mount the rules of democracy declined.

Libel suits launched by Thaksin against the media and private individuals became commonplace.

Yes, the media was free to say what they wanted but most could simply not afford it. Thaksin’s gang of lawyers had forced the media to ‘self censor’ to avoid costly and time consuming legal battles.

Thaksin had also dismantled the foundations of Thailand’s democratic institutions. The ranks of the judiciary, the Senate, and the now disgraced Election Commission were all swollen with Thaksin’s friends and family.

The most recent snap election that Thaksin called to defuse the myriad of calls for him to step down resulted in a boycotted single-party election, massive claims of fraud, a rare intervention by the king, the election’s subsequent annulment, and finally the jailing of pro-Thaksin Election Commission officials for malfeasance.

Thaksin’s stubborn grip on power had simply destroyed the democratic process.

Was it a Revolution then?

Maybe not a textbook revolution but there has been widespread public support.

The tanks forming road blocks around the seat of political power, Government House, have been covered in flowers in a spontaneous gesture by the residents of Bangkok.

The military has reciprocated with its own symbolic gesture of alliance to the people. Although the troops are combat ready, most have removed their ammunition clips from their rifles.

Yes, they are armed, but not armed against the people.

The justification for seizing power, as claimed by the military’s new Committee for Democratic Reform, was based upon welfare of the people.

Speculation that the highly polarized political crisis would lead to violent clashes was not just speculation but the public was resigned to the inevitability of violence.

Violent incidents between pro and anti-Thaksin camps were growing in frequency and in brutality in the weeks before military take over.

A large anti-Thaksin protest by the People’s Alliance for Democracy that was scheduled to take place if the military intervention had not happened had the very real possibility of massive bloodshed.

Rumours were circulating that a well armed division of Forestry Police were being transported to Bangkok put down the protest.

Because widespread violence was expected the military claims they were duty bound to intervene.

The highly influential retired General, Prem Tinsulanonda, just over a month before the military action, gave a speech to cadets telling them that the loyalty of the military is to the king first, the citizens next, and the government trailing behind in a distant third.

It seems as though Prem’s words were not just hollow rhetoric but a strategic declaration of military alignment with the growing number of dissatisfied citizens.

A final, and extremely important, indication that the military action was on behalf of the people was the action’s royal approval. It is well known in Thailand that the King’s approval can legitimize or topple a government.

During the last major conflict that brought soldiers onto the streets, in 1991, the King intervened with some ‘words of advice’ and diffused a violent power struggle.

It was vitally important for the military leaders to have royal approval but, more revealing, is that royal approval would not likely have been granted if the overthrow of the government wasn’t in the people’s best interest.

During the first week of military rule there has been a palpable sense of revolution on the Bangkok streets.

The challenge is now for the military to maintain that feeling of revolution. Yet to maintain the revolutionary goodwill it will require the military to step down and return the political realm to civilian control.

If the feeling of revolution is lost then a true textbook coup d’etat has taken place and an era of military rule, an era of dictatorship, has began.